Friday, December 23, 2005

The new RSS feed is http://www.internettime.com/wordpress/wp-rss2.php

This Blog won't disappear but all new posts will appear on the new blog.

|

Jay Cross

New blog Links & more Subscribe to the BlogRecent Photos |

Global Learning: Mr Cross, currently you are working on a book about informal learning. How do you define informal learning?More

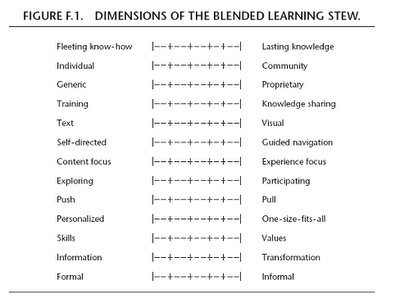

Jay Cross: Well, I had to redefine all learning in order to write the book because the world is changing so fast. The concepts we had when knowledge was fixed in place, like something you could put in a library, don’t work anymore. So I look at all learning as adaptation to the communities that matter to you, to your ecosystems, if you will. Informal learning is simply that, which is not directed by an organisation or somebody in a control position.

Homeland used to mean "the country where somebody was born or where somebody lives and feels that he or she belongs." Now the accent is on home. Imagine these rag-top terrorist bastards invading your house, smashing your stuff, raping the women, killing the children, and blowing the place to smithereens by detonating a truckload of plastic explosive in your driveway.

Homeland used to mean "the country where somebody was born or where somebody lives and feels that he or she belongs." Now the accent is on home. Imagine these rag-top terrorist bastards invading your house, smashing your stuff, raping the women, killing the children, and blowing the place to smithereens by detonating a truckload of plastic explosive in your driveway.

Last year's conference on empathy in the brain and in art was one of the more meaningful days of 2005 for me.Understanding how chocolate, champagne or Channel No. 5 can elicit intense reactions and enhance long-term memories promises to guide scientists in their research of how pleasure centers and the memory system in the brain are connected. Likewise, chefs, vintners and perfumers can learn from scientists how our brains respond to their products.

At the day-long conference, speakers will range from Yale University’s Dana M. Small, an expert in how the brain processes flavor, to San Francisco Zen Center’s Ed Epse Brown, a priest, cook and author.

Slide after slide of bulleted sentence fragments is an awful thing to sit through. If the speaker giving the presentation reads them to you word for word, it makes a bad spectacle even worse. Regardless of these unpleasantries, PowerPoint has become the language of business.

PowerPoint also happens to be learning’s most popular authoring tool. Many software packages enable learning and development leaders to narrate a PowerPoint presentation and upload it to the Web. The problem is that if live lectures are ineffective, prerecorded ones online are going to be even more ineffective. Unfortunately, being a subject-matter expert doesn’t necessarily make someone an expert public speaker. Sadly, many experts think the purpose of a PowerPoint presentation is to expose the audience to content and pure information—as if emotion plays no part in getting a message across.

However, it makes no more sense to blame PowerPoint for boring presentations than to blame fountain pens for forgery.

Steve Denning, the author of several books on storytelling, recalls not being able to get fully engaged into someone’s PowerPoint presentation. He recognized that PowerPoint can be too concrete, and therefore, he abandoned PowerPoint in his own presentations in favor of telling stories. No one missed it. When you hear a powerful story, you internalize it. Your imagination makes it your story, and that’s something that will stick with you.

It makes no more sense to blame PowerPoint for boring prsentations than to blame fountain pens for forgery.Cliff Atkinson’s book “Beyond Bullet Points: Using Microsoft PowerPoint to Create Presentations That Inform, Motivate and Inspire” shows how to use Hollywood’s script-writing techniques to focus your ideas, how to use storyboards to establish clarity and how to properly produce the script so that it best engages the audience.

Atkinson recently told me the story of a presentation that made a $250 million difference. Attorney Mark Lanier pled the case against Merck in the first Vioxx-related death trial, brought by the widow of a man who died of a heart attack that she believed was caused by the painkiller. Before preparing his presentation, he read “Beyond Bullet Points,” and invited Atkinson to Houston to lend a hand in putting his presentation together.

“We used the three-step approach from the book,” Atkinson said. “Then (Lanier’s) flawless delivery took the experience beyond what I imagined possible. He masterfully framed his argument with an even flow of projected images and blended it with personal stories, physical props, a flip chart, a tablet PC, a document projector and a deeply personal connection with his audience.”

Fortune magazine’s coverage of the trial describing Lanier’s presentation said, “The attorney for the plaintiff presented simple and emotional stories that strongly contrasted with Merck’s appeals to colorless reason.” Fortune reported that Lanier “gave a frighteningly powerful and skillful opening statement. Speaking…without notes and in gloriously plain English, and accompanying nearly every point with imaginative, easily understood (if often hokey) slides and overhead projections, Lanier, a part-time Baptist preacher, took on Merck and its former CEO Ray Gilmartin with merciless, spellbinding savagery.”

Lanier’s technique was persuasive and aimed to get the jurors to believe in his “simple, alluring and emotionally cathartic stories, versus Merck’s appeals to colorless, heavy-going, soporific reason. Lanier is inviting the jurors to join him on a bracing mission to catch a wrongdoer and bring him to justice.” The Texas jury awarded the widow $253.4 million.

You may be thinking, “I don’t have time to do something that elaborate.” Put that in perspective: If you spend months on a complex project, isn’t it worth a few days to wrap up the results into an effective presentation? If you’re using PowerPoint as an authoring system, remember this: A presentation and self-directed learning are two totally different experiences, and the fact that they both may be in PowerPoint doesn’t change that. For compelling presentations, follow the advice in “Beyond Bullet Points.” And for training that works, follow the tenets of sound instructional design.

That's it.

That's it. Normally, I would not expect to get many chuckles from a 186-page report entitled Learning styles and pedagogy post-16 learning A systematic and critical review, 2004, by Frank Coffield, Institute of Education, University of London; David Moseley, University of Newcastle; Elaine Hall, University of Newcastle; Kathryn Ecclestone, University of Exeter. This is an exception.

Normally, I would not expect to get many chuckles from a 186-page report entitled Learning styles and pedagogy post-16 learning A systematic and critical review, 2004, by Frank Coffield, Institute of Education, University of London; David Moseley, University of Newcastle; Elaine Hall, University of Newcastle; Kathryn Ecclestone, University of Exeter. This is an exception.| About Us | Contact Us | Home | |