Sunday, January 23, 2005

I finished reading Malcolm Gladwell's Blink about ten minutes ago. In a post titled Thin Slices, I described the first couple of chapters; now I'll give you my take on the rest of the book. Related blog entries here are First Impression and Automatic Decision-Making.

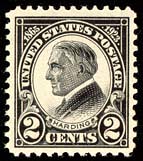

Gladwell tells the story of Warren G. Harding, a guy who looked presidential but was a total doofus. No one could get beyond their first impression. The Implicit Association Test analyzes your subconscious biases -- so well that you can't fake it. You can take it online. I found I was biased against fat people even though I could stand to drop 25 pounds myself. Bottom line: you don't know what you're thinking.

Gladwell tells the story of Warren G. Harding, a guy who looked presidential but was a total doofus. No one could get beyond their first impression. The Implicit Association Test analyzes your subconscious biases -- so well that you can't fake it. You can take it online. I found I was biased against fat people even though I could stand to drop 25 pounds myself. Bottom line: you don't know what you're thinking.

Then we visit a commando vet who outfoxed the top U,S, military in an elaborate war game which sounds like a dry run for invading Iraq. The vet made room for spontaneity; the establishment used systems. More was less. Too many options fuzz up your thinking. The bad guys started by demolishing the U.S. fleet with cruise missiles (having zeroed in on their position with stealth fishing boats.) Hive mind trumps information overload.

A researcher sets up a tasting table at Draeger's in Menlo Park (a great grocery store, if you're ever in the neighborhood). One day the researcher offers tastes of six jams. Another day, there's a choice of 24 jams. More people buy jam when presented with fewer choices. No one can deal with 24 choices; they fear making the wrong decision.

We're introduced to Kenna, a singer the record producers love but the market researchers pan. It's like the Pepsi Challenge and New Coke. A first taste is different from drinking or listening to the whole thing. Furthermore, experts grow repertoire and they're the only people who can tell you why they react they do. Conversation with a couple of amazingly analytical food tasters leads Gladwell to conclude:

Our unconscious reactions come out of a locked room, and we can't look inside that room. But with experience we become expert at using our behavior and our training to interpret -- and decode -- what lies behind our snap judgments and first imporessions. It's a lot like what people do when they are in psychoanalysis: they spend years analyzing their unconsicous with the help of a trained therapist until they being to get a sense of how their mind works.Gladwell overworks the shooting of Amadou Diallo: 41 bullets fired at an unarmed man. In short form: the cops misread the situation. The shooters got so worked up, they were suffering from momentary autism. Faulty assumptions and shared hysteria had them watching their own movies rather than judging what was really going on.

A few pages into the Diallo story, I hit one of these small-world anomalies that seem to be the hallmark of my existence. There are page after page of stories about Paul Ekman, the facial recognition expert. Paul was the last act at the Neuroesthetics Conference I attended in Berkeley one week ago today.

A few pages into the Diallo story, I hit one of these small-world anomalies that seem to be the hallmark of my existence. There are page after page of stories about Paul Ekman, the facial recognition expert. Paul was the last act at the Neuroesthetics Conference I attended in Berkeley one week ago today.

That's not the coincidence.

Ekman's mentor, Silvan Tomkins, more or less invented reading human emotions. Gladwell lauds Tomkins as a mind reader, perhaps the greatest of them all. Following in Tomkins' footsteps, Ekman found that changing one's expression changes the autonomic nervous system. I have read Volume III of Tomkins' monumental Affect, Imagery, Consciousness. In fact, I've heard Tomkins tell the joke form of Ekman's finding. Two psychologists meet on the street. "You're fine. How am I?" Tomkins was my psychology prof at Princeton. If I'd only realized he was such hot stuff.

Gladwell wraps things up with a cautionary tale. A woman auditions to play first trombone for the Munich Philharmonic. Candidates for the position play behind a screen, to eliminate favoritism since one of the players is known to the orchestra. Surprise, surprise, the woman plays so well they send everyone else home early. Then they try to oust her by any means possible. Lawsuits ensue. It's a great story and her husband wrote it up for his website; see You Sound Like a Ladies Orchestra. Gladwell ends on this story, saying:

When the screen created a pur Blink moment, a small miracle happened, the kind of small miracle that is always possible when we take charge of the first two seconds: they saw her for who she truly was.

Blink will make Malcolm Gladwell the guru speaker of the year. He seems like a very nice fellow, and I wish him well. He is a compelling storyteller. The telling and retelling of his parables will awaken many people, particularly hard-assed business types, to the legitimacy of intuition as a mode of thinking.

The downside is that Gladwell abandons us after telling the stories. There's no conclusion. There's no theory. There's no advice on how to take advantage of thin-slicing, no suggestions on how to attain wisdom. In fact, "thin slicing" is destined to become a buzz word but it is nearly meaningless.

I find Richard Sapolsky's descriptions of focus and stress more illuminating than Glawell's. Michael Gazzaniga's The Mind's Past gave me a framework for thinking about the subconscious.

The Mind's Past talks about the internal conversation always going on in our heads. Listen for a minute. Yeah, that's it. The book also describes a mediator between the brain and the mind called "the interpreter."

Let's call the subconscious, autonomic brain simply "the brain;" it's attached directly to the senses. The conscious, aware portion of our gray matter, we'll call "mind."

The brain gets sensations first. It rejects most of this sensory input and makes basic decisions about what to do next. Later, "the interpreter" creates a story to provide a rational explanation. The interpreter weaves together a plausible story to bullshit the mind into believing it's rational and in control. In fact, most decisions are made before they enter consciousness.

Got that? Your don't make up your mind; your brain makes up your mind. Its interpreter spins yarns the way you do when recounting a dream. A lot more of the brain comes with mechanics "factory-installed" than we like to think. As Bernard Malamud has observed, "All biography is ultimately fiction." Gazzaniga says, "Autobiography is hopelessly inventive."

Changing one's mind consists of convincing the interpreter that the facts of the matter or memories of the past or one's self-image or the rules of the game haved shifted. The changed interpreter puts a different spin on the stories it tells, for those stories must seem internally consistent. The stories must also maintain the fiction that the mind is calling the shots, not the brain.

What might be the nature of this interpreter? Clearly, it needs an image of who its owner is and what the owner is capable of. I'll call this the secret resume, for like a printed resume, it's a very selective and self-serving sense of one's past. The interpreter also needs a worldview or meme library, the rules by which things operate. And the interpreter must retrieve memories, for this is the content of thinking. Changing either the secret resume, the worldview, or the memories changes the interpreter's stories. This is learning.

1 Comments:

Bill, that's two of us. As I said, "The downside is that Gladwell abandons us after telling the stories. There's no conclusion. There's no theory. There's no advice on how to take advantage of thin-slicing, no suggestions on how to attain wisdom. In fact, 'thin slicing' is destined to become a buzz word but it is nearly meaningless."

Yesterday I read an interesting passage in Ellen Langer's book On Becoming an Artist. She describes how we con ourselves into thinking we're hot-shot forecasters because things seem logical when we look back on them.

For example, "Richard Feynman was asked a question about the use of data to verify an idea. To the surprise of his audience, his reply began with a discourse on license plates: 'You know, the most amazing thing happened to me tonight. I was coming here, on the way to the lecture, and I came in through the parking lot. And you won't believe what happened. I saw a car with the license plate ARW 357. Can you imagine? Of all the millions of license plates in the state, what was the chance that I would see that particular one tonight? Amazing!'" The odds are 18,000,000:1.

Langer concludes that "All events are improbably, so why do we think we can predict events in the future?"

Post a Comment

<< Home