Wednesday, July 27, 2005

On Monday, research for my book on Informal Learning took me down the San Francisco Peninsula to the fabled Palo Alto Research Center, née Xerox PARC, birthplace of the GUI, the personal computer, the laser printer, the local area network, and ubiquitous computing. While PARC has produced nearly 30 new companies and made significant scientific contributions in fields as diverse as materials science, distributed computing, linguistics and sociology, it is also the ignominious subject of the book Fumbling the Future.

On Monday, research for my book on Informal Learning took me down the San Francisco Peninsula to the fabled Palo Alto Research Center, née Xerox PARC, birthplace of the GUI, the personal computer, the laser printer, the local area network, and ubiquitous computing. While PARC has produced nearly 30 new companies and made significant scientific contributions in fields as diverse as materials science, distributed computing, linguistics and sociology, it is also the ignominious subject of the book Fumbling the Future. Horses grazed in the fields alongside Coyote Hill Road, the tail end of a bucolic drive through the rolling hills of Leland Stanford's former farm. Up ahead, PARC's low-slung buildings still look modern after nearly four decades. The scientists and researchers here are still turning out incredibly weird and important stuff, but I haven't come to talk about smart matter, vertical cavity lasers, electrostatic traveling waves, collaborative sensing, or amophous silicon.

Horses grazed in the fields alongside Coyote Hill Road, the tail end of a bucolic drive through the rolling hills of Leland Stanford's former farm. Up ahead, PARC's low-slung buildings still look modern after nearly four decades. The scientists and researchers here are still turning out incredibly weird and important stuff, but I haven't come to talk about smart matter, vertical cavity lasers, electrostatic traveling waves, collaborative sensing, or amophous silicon.What drew me to PARC was the opportunity to talk with the former Dean of the School of Engineering at Stanford about an amazingly successful distance learning program he created in 1972. (I was enthralled, but that's another story.) In our quest for the latest and greatest, it's easy to forget that our generation didn't invent wisdom. Civilization has been churning out great ideas for centuries. A person born a hundred years ago is probably pushing up daisies, but many hundred year-old books are as fresh as, at the risk of repeating myself, a daisy.

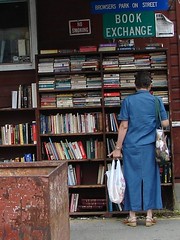

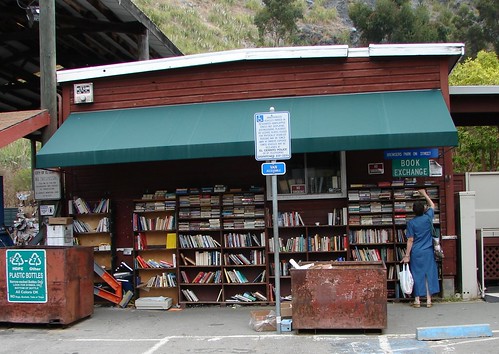

A few days later, I took a 30-minute detour the Book Exchange at the Recycling Center in El Cerrito. "Exchange" is not quite the right term, for many of the people perusing the shelves have brought nothing to trade, and many of the people dropping off books take nothing away. I love this place. Great ideas. Free.

A few days later, I took a 30-minute detour the Book Exchange at the Recycling Center in El Cerrito. "Exchange" is not quite the right term, for many of the people perusing the shelves have brought nothing to trade, and many of the people dropping off books take nothing away. I love this place. Great ideas. Free. The

The This is what abundance is all about. Free content! There are free jewels on the web, and books for the taking at the recycling center.

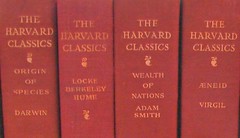

A mail order firm sold the "Five-foot Shelf" of Harvard Classics at the height of the depression. (Robert Collier's 1931 book on how he wrote compelling direct mail taught me how to write letters that sell; I have a summary here.) I pulled these four out of the dumpster and brought them home.

A mail order firm sold the "Five-foot Shelf" of Harvard Classics at the height of the depression. (Robert Collier's 1931 book on how he wrote compelling direct mail taught me how to write letters that sell; I have a summary here.) I pulled these four out of the dumpster and brought them home.- The Origin of Species, Darwin

- Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith

- Aeneid, Virgil

- Locke, Berkeley, Hume

For good measure, I also grabbed The Closing of the American Mind (Bloom), The Voice of Experience (Laing), Transitions (Bridges), Selected Papers of Bertand Russell, and Havelock Ellis's The Dance of Life.

It's not as if I need more books in my life. Rather, I want to write the best-informed, exciting-to-read books for my readers, and there's always something new to learn.

Next Day

Which should I throw in my shoulder-bag to read in my doctor's waiting room, The Dance of Life or today's New York Times? The Dance of Life dates from 1923. The Times arrived here at 4:30 this morning. Clearly the Times is the more, uh, timely, but since ideas can remain fresh for centuries, that doesn't make much difference.

The New York Times is an old, familiar friend. Without taking it out of the bag, I know that today's paper will cover such familiar stories as the morass in Iraq, economic dislocations somewhere, NASA and the shuttle, abortion, Israel, fundamentalism and its sister terrorism, blah, blah, blah. You can't learn something you already know. At most, I might learn another one or two percent of any of these never-ending sagas.

The Dance of Life is a mystery to me. Havelock Ellis has a familiar ring to it, from where I do not know. The book is part of the Modern Library Series, so Ellis is among the company of Aristotle, Balzac, Chaucer, Dante, Emerson, Faulkner, and other notables. There's a chapter entitled The Art of Writing, and I happen to be writing a book. Ellis is probably going to take me out of my comfort zone. I'm more likely to learn from The Dance of Life than from today's newspaper.

"From time to time we are solmnly warned that in the hands of modern writers language has fallen into a morbid state," reads the first sentence in chapter on The Art of Writing. He writes that, "Men are always apt to bow down before the superior might of their ancestors" and that they were "giants." Bones from ancient crypts show that we are larger than those who came before us, but "Fortunately for the vitality of tradition, we cherish a wholesome distrust of science." Things don't seem to have changed much in the last 80 years. What's more, the author has a tongue-in-cheek style of skewering opposing views. When I get home, I take a few minutes to get a second opinion on whether I want to invest more time in this guy.

Amazon's A9 search tool is great for getting a mental snapshot of an author. Soon I'm reading...

Havelock Ellis (1859 – 1939), the great pioneering sexologist, has always been much more appreciated in America than in Britain. There are, I believe, two reasons for this disparity. In the first place, Americans are notoriously open to new ideas, hence their enthusiastic reception of Freud - although he observed sourly that they didn't realise that he was bringing them the plague. The other, more demonstrable reason for Ellis's wider acceptance in America was the outcome of the famous Bedborough obscenity case in 1897.

In 1896 Ellis, in collaboration with John Addington Symonds (who died prematurely in 1893) published in Germany Das Kontrare Geschlechtesgefuhl (Contrary Sexual Feeling). Although it seems to have been the first scientific work to treat homosexuality neither as a disease nor a crime, the book was reviewed respectfully and caused no particular stir. But Ellis reckoned without British hypocrisy when he allowed what was to become the first volume of Studies in the Psychology of Sex to be published in England the following year.

Ah, yes, now I remember. Ellis, the radical sexologist. Another source relates...

Throughout his life, Ellis sought to bring science and mysticism closer together. His major work in this vein, and also his best-selling book, was The Dance of Life (1923). In it he promoted the constant development of the self through a variety of "arts," including thinking, morals, and dance.These quotations from Brainy Quote aroused my interest:

- A sublime faith in human imbecility has seldom led those who cherish it astray.

- All civilization has from time to time become a thin crust over a volcano of revolution.

- All the art of living lies in a fine mingling of letting go and holding on.

- Dreams are real as long as they last. Can we say more of life?

- Every artist writes his own autobiography.

- It has always been difficult for Man to realize that his life is all an art.

- The byproduct is sometimes more valuable than the product.

- The greatest task before civilization at present is to make machines what they ought to be, the slaves, instead of the masters of men.

- The sun, the moon and the stars would have disappeared long ago... had they happened to be within the reach of predatory human hands.

Lunchtime with Havelock

Ellis tells us that personality is not something that can be sought; it is a radiance that is diffused spontaneously. A writer should use the language, not conform to petty rules. Take the solemn warning against the split infinitive. It's a superstition derived from Latin, where infinitives are one word, not two, and cannot be split. Same deal with ending with a preposition, which is impossible to do in French. The conclusion: There is only one rule to follow here--and it is simply the rule in every part of art--to know what one is doing, not to go sheep-like with the flock, ignorantly, unthinkingly, heedlessly, but to mould speech to expression the most truly one knows how.

Just as the man who, having out of sheer ignorance eaten the wrong end of his asparagus, was thenceforth compelled to declare that he preferred that end, so it is with our race in the matter of spelling; our ancestors, by chance or by ignorance, tended to adopt certain forms of spelling and we, their children, are forced to declare that we prefer those forms.

Yesterday I was walking with Elizabeth in a former Navy shipyard that has been converted into a pocket-park and future bird sanctuary. For me, new places inspire fresh thoughts. We were talking about communities of practice. I said I was learning to be an author, putting aside the roles of consultant, learning expert, and marketing exec. And at lunch I realized the Ellis was teaching me about my craft. I'm learning the new rules.

Yesterday I was walking with Elizabeth in a former Navy shipyard that has been converted into a pocket-park and future bird sanctuary. For me, new places inspire fresh thoughts. We were talking about communities of practice. I said I was learning to be an author, putting aside the roles of consultant, learning expert, and marketing exec. And at lunch I realized the Ellis was teaching me about my craft. I'm learning the new rules.In his Preface, Ellis says he has realized that the writer need not always finish his work in every detail; by not doing so he may succeed in making the spectator his co-worker, and put into his hands the tool to carry on the work which, as it lies before him, beheath its veil of yet partly unworked material, still stretches into infinity. I am right with him on this. Learning is co-creation. Positioning one's writing as experimental welcomes input from the learner; finalizing the same writing signals no input is welcome -- this is already dogma. (This post is in beta. Send me your comments.)

The Dance of Life is going to the downstairs bookshelf. I may get back to it; The Art of Thinking sounds interesting. Then again, I may not. So many books, so little time. My muse is calling. Sunset is the promise of dawn.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home