Tuesday, September 06, 2005

A Birth of Tragedy

Our thoughts are dominated by the aftermath of the disaster last week that put New Orleans underwater. Four years after 9/11, the death of 3,000 people in the violent collapse of the World Trade Center still haunts New Yorkers. These events pale in comparison to World War II.

Enormity of World War II

For every individual who perished on 9/11, twenty-thousand people perished in World War II. Sixty years later, echoes of this bloodiest war in history still shape how most of us perceive the world.

Do or die

World War II wasn’t like Vietnam or Iraq. Neither the Viet Cong nor the Iraqis threatened America’s borders. World War II was an all-out struggle for civilization. Mines floated just inside the Golden Gate to protect against Japanese invaders. Europe was overrun by Nazis, England holding on by a thread. If we didn’t win this one, everyone on the planet would be eating sauerkraut and raw fish.

Winning ways

What could be more wonderful than saving the world from the clutches of storm-troopers, kamikazes, brutes, and fascists? The allies won with command and control, strategy and tactics, clear lines of authority and obedience to orders, regimentation and standardization, officers and staff. Don’t question authority; just do what you’re told. Hold that thought.

Behaviorism

B.F. Skinner and his fellow behaviorists dominated academic psychology during and after World War II. They held that one could study psychology by observing behavior alone, paying no attention to internal mental states. People, like Pavlov’s dogs, had no free will. They do what they are conditioned to do. You could study the behavior of pigeons and rats, and generalize your findings to humans. Behaviorists believed themselves “scientific” because they only dealt with things they could see: no nasty feelings, beliefs, or other nasty intangibles could cloud the supposed objectivity of their results. Materialism reigned; our humanity was denied.

Computers

My first job out of college was selling and installing mainframe computers. Upon hearing what I did for a living, some people wondered if I were a math savant or into theoretical physics. Computers were thought to be “electronic brains” that might overtake human brains at some point. Most folks did not understand computers at all but they knew they were precise and that deep inside, everything was ultimately a one or a zero.

Three factors

The War, behaviorism, and computers played major roles in shaping society’s current mental models. All three are poster children for top-down control, rigid organization, and unquestioning obedience. Their lessons have spilled over into our working lives. The ideal worker conformed to expectations, didn’t question the status quo, and rarely got out of line.

Corporations follow the military

Corporations that were out to win mimicked the military formula, demanding loyalty and mindless obedience. Organizations adopted rigid command and control hierarchies. They launched campaigns to beat the competition. They also copied military training.

Military training

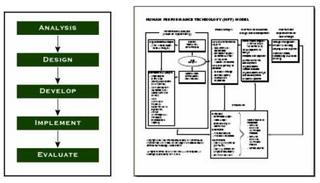

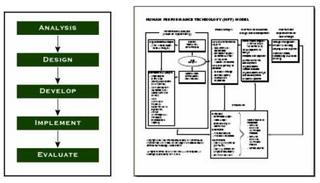

The United States had no standing army when the bombing of Pearl Harbor brought it to war. Millions of farm boys and insurance agents needed to become instant soldiers. The military invented the training film and efficient methods of designing training materials. Here are the “ADDIE” model and a recent iteration of ISPI’s human performance technology model.

Where are the people?

These quite influential models are presented as computer-style flowcharts. They box the design process into steps and deal with them one at a time. There’s no unity, nothing working together here. You finish one step and go on to the next. Like behaviorist psychology, there’s no emotion. People’s feelings count for nothing. It’s as if the workers being trained are robots or zombies. And what about the impact of what’s outside of the flowchart? These models don’t map to reality.

The Whole Earth

In 1966, Stewart Brand successfully lobbied NASA to release then-rumored photographs of earth from space, hoping that visualizing “spaceship earth” would raise the global consciousness of the environment and ecology. It worked. The Whole Earth Catalog listed items relevant to independent education. The preface to the first edition lauds the potential of the individual and the failure of major institutions:

In 1966, Stewart Brand successfully lobbied NASA to release then-rumored photographs of earth from space, hoping that visualizing “spaceship earth” would raise the global consciousness of the environment and ecology. It worked. The Whole Earth Catalog listed items relevant to independent education. The preface to the first edition lauds the potential of the individual and the failure of major institutions:

We are as gods and might as well get good at it. So far, remotely done power and glory - as via government, big business, formal education, church - has succeeded to the point where gross defects obscure actual gains. In response to this dilemma and to these gains a realm of intimate, personal power is developing — power of the individual to conduct his own education, find his own inspiration, shape his own environment, and share his adventure with whoever is interested.

Control from the bottom up challenged the supremacy of top-down control. We’re all in this together, and now we saw proof that earth was not boundless.

A physics lesson

It took more than a generation for the conceptual breakthroughs of Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr to seep into the public consciousness. The certainty of Isaac Newton’s clockwork universe crumbled in the face of relativity and uncertainty. We discovered that we hadn’t figured how the earth functioned. We masters of the universe were but pebbles in a stream.

Vietnam

America’s defeat at the hands of indigenous troops dressed in black pajamas brought the simplistic military calculus into question. A systems view provided better explanations of how the world worked. Counting things up did not make them real. Whiz kids at the Pentagon were too distant to understand the context. The military machine turned out not to be a machine at all.

Living systems

Organizations are living systems, not machines. The people within them are sentient, emotional, and often irrational human organisms. How they learn is anything but concrete and lockstep. Dipping into the rapid flow of knowledge streaming by, workers pull up a ladle of knowledge never seen before, but knowledge of a world now downstream. The ADDIE model breaks down in times of change or when we no longer buy the concept that an expert needs analyst can somehow suck the important knowledge out of a subject matter expect and encapsulate it into a training intervention. Furthermore, it is folly to imagine that anyone can “control” other human beings. We can give them a little shove here and there but that’s about it.

Landscape design

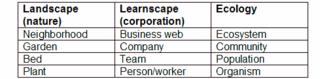

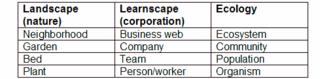

Put on your sun hat and boots, for we’re going to look at the site for our garden. Permit me the liberty of comparing our landscape project with nature at large and with a corporate organization since both are living systems:

The Designer's Role

As a landscape designer, my goal is to conceptualize a harmonious, unified, pleasing garden that makes the most of the site at hand. As an enlightened instructional designer, my goal is to create a learning environment that advances the organization’s mission by nurturing the growth of its people.

Unity

Great gardens express a unity of design. Gardens are whole, not a series of independent pieces. Unity “is a quality found in all great landscapes, based on the rhythm of natural land-form, the domination of one type of vegetation and the fact that human use and buildings have kept in sympathy with their surroundings. All the great gardens of the world have a unity both of execution and conception which shows that they were created in singleness of thought.” (Crowe, 1994)

Learnscapes

Learning environments, which I’ll dub learnscapes, are like landscapes. They make sense as a whole, not simply a bunch of independent courses and workshops. As in nature, you don’t get very far if you think only of people, ignoring the community in which they are interconnected. We can establish the starting conditions, but then we have to let the plants (or the people) grow as they will. Each organism contains it own feedback loops; adaptation is their destiny. Shouting at them won’t turn roses into rhubarb or artists into engineers, for a rose is a rose is a rose, and a person comes with hard-wired aspects as well as flexibility.

Out of control

Shouting at it does not shorten an organism’s route to maturity. Things grow by the pace of their own internal clock. Gardeners don’t control plants, and managers don’t control people. The most that either can do is nurture growth by supplying nutrients and pulling weeds. Gardeners and managers have influence but not absolute authority. They can’t make a plant fit into the landscape or a person fit into a team.

Fuzzy picture of outcomes

Because landscapes and learningscapes are co-created with nature, the designer never knows precisely what to expect. Photorealistic predictions of the future appearance of gardens and organizations are folly. The designer must work to satisfy aspirations and values, not precise outcomes. Man plans; God laughs. No learnscape will survive when the levee breaks or the ground quakes.

Processes, not events

The late Peter Henschel, former head of the Institute for Research on Learning, said that “The manager’s core work in this new economy is to create and support a work environment that nurtures continuous learning. Doing this well moves us closer to having an advantage in the never-ending search for talent.” How else could it be? Neither nature nor the workplace will cooperate by going into suspended animation so we can tweak the details without things changing all the time. Everything flows. You go with the flow or you are out of it. Every learnscape has a history and a future, but the present is a moving target. (Peter Henschel, in LiNEzine).

Learning = work, work = learning

In a knowledge economy, learning and work are one and the same. Here’s Peter Henschel again, saying “By sheer force of habit, we often substitute training for real learning. Managers often think training leads to learning or, worse, that training is learning. But people do not really learn with classroom models of training that happen episodically. These models are only part of the picture. Asking for more training is definitely not enough—it isn’t even close.”

Oversimplification

Human minds seek to simplify their surroundings. Otherwise the cacophony of waves bouncing off our heads would drive us mad. Deductive reasoning filters reality by rejecting anything that doesn’t fit an if…then…else formula. This is like the behaviorists denying the impact of mental processes because they could not see them.

No shit, Sherlock

Clay Shirky writes that “The great popularizer of this [over-reliance on deductive reasoning] was Arthur Conan Doyle, whose Sherlock Holmes stories have done more damage to people's understanding of human intelligence than anyone other than Rene Descartes. Doyle has convinced generations of readers that what seriously smart people do when they think is to arrive at inevitable conclusions by linking antecedent facts. As Holmes famously put it ‘when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.’"

How we think

He continues, “In the real world, we are usually operating with partial, inconclusive or context-sensitive information. When we have to make a decision based on this information, we guess, extrapolate, intuit, we do what we did last time, we do what we think our friends would do or what Jesus or Joan Jett would have done, we do all of those things and more, but we almost never use actual deductive logic.”

Over…for now

Courses end; learnscapes persist. One should stretch an analogy as much as appropriate but no further. Organizations and their members are living things, and the landscape/learnscape analogy invites us to consider nature, symbiosis, interconnections, genetic make-up, adaptation, the change of seasons, and life cycles. People are not plants, so the analogy doesn’t stretch into self-expression, thinking, identity, personality, and other solely human traits.

In the mechanical world, I’d wrap this up with a conclusion. In a natural world, I know that this is but one step on a long journey. Nothing ends. So I’ll end here for now and pick up later when the situation is ripe.

Our thoughts are dominated by the aftermath of the disaster last week that put New Orleans underwater. Four years after 9/11, the death of 3,000 people in the violent collapse of the World Trade Center still haunts New Yorkers. These events pale in comparison to World War II.

Enormity of World War II

For every individual who perished on 9/11, twenty-thousand people perished in World War II. Sixty years later, echoes of this bloodiest war in history still shape how most of us perceive the world.

Do or die

World War II wasn’t like Vietnam or Iraq. Neither the Viet Cong nor the Iraqis threatened America’s borders. World War II was an all-out struggle for civilization. Mines floated just inside the Golden Gate to protect against Japanese invaders. Europe was overrun by Nazis, England holding on by a thread. If we didn’t win this one, everyone on the planet would be eating sauerkraut and raw fish.

Winning ways

What could be more wonderful than saving the world from the clutches of storm-troopers, kamikazes, brutes, and fascists? The allies won with command and control, strategy and tactics, clear lines of authority and obedience to orders, regimentation and standardization, officers and staff. Don’t question authority; just do what you’re told. Hold that thought.

Behaviorism

B.F. Skinner and his fellow behaviorists dominated academic psychology during and after World War II. They held that one could study psychology by observing behavior alone, paying no attention to internal mental states. People, like Pavlov’s dogs, had no free will. They do what they are conditioned to do. You could study the behavior of pigeons and rats, and generalize your findings to humans. Behaviorists believed themselves “scientific” because they only dealt with things they could see: no nasty feelings, beliefs, or other nasty intangibles could cloud the supposed objectivity of their results. Materialism reigned; our humanity was denied.

Computers

My first job out of college was selling and installing mainframe computers. Upon hearing what I did for a living, some people wondered if I were a math savant or into theoretical physics. Computers were thought to be “electronic brains” that might overtake human brains at some point. Most folks did not understand computers at all but they knew they were precise and that deep inside, everything was ultimately a one or a zero.

Three factors

The War, behaviorism, and computers played major roles in shaping society’s current mental models. All three are poster children for top-down control, rigid organization, and unquestioning obedience. Their lessons have spilled over into our working lives. The ideal worker conformed to expectations, didn’t question the status quo, and rarely got out of line.

Corporations follow the military

Corporations that were out to win mimicked the military formula, demanding loyalty and mindless obedience. Organizations adopted rigid command and control hierarchies. They launched campaigns to beat the competition. They also copied military training.

Military training

The United States had no standing army when the bombing of Pearl Harbor brought it to war. Millions of farm boys and insurance agents needed to become instant soldiers. The military invented the training film and efficient methods of designing training materials. Here are the “ADDIE” model and a recent iteration of ISPI’s human performance technology model.

Where are the people?

These quite influential models are presented as computer-style flowcharts. They box the design process into steps and deal with them one at a time. There’s no unity, nothing working together here. You finish one step and go on to the next. Like behaviorist psychology, there’s no emotion. People’s feelings count for nothing. It’s as if the workers being trained are robots or zombies. And what about the impact of what’s outside of the flowchart? These models don’t map to reality.

The Whole Earth

In 1966, Stewart Brand successfully lobbied NASA to release then-rumored photographs of earth from space, hoping that visualizing “spaceship earth” would raise the global consciousness of the environment and ecology. It worked. The Whole Earth Catalog listed items relevant to independent education. The preface to the first edition lauds the potential of the individual and the failure of major institutions:

In 1966, Stewart Brand successfully lobbied NASA to release then-rumored photographs of earth from space, hoping that visualizing “spaceship earth” would raise the global consciousness of the environment and ecology. It worked. The Whole Earth Catalog listed items relevant to independent education. The preface to the first edition lauds the potential of the individual and the failure of major institutions:We are as gods and might as well get good at it. So far, remotely done power and glory - as via government, big business, formal education, church - has succeeded to the point where gross defects obscure actual gains. In response to this dilemma and to these gains a realm of intimate, personal power is developing — power of the individual to conduct his own education, find his own inspiration, shape his own environment, and share his adventure with whoever is interested.

Control from the bottom up challenged the supremacy of top-down control. We’re all in this together, and now we saw proof that earth was not boundless.

A physics lesson

It took more than a generation for the conceptual breakthroughs of Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr to seep into the public consciousness. The certainty of Isaac Newton’s clockwork universe crumbled in the face of relativity and uncertainty. We discovered that we hadn’t figured how the earth functioned. We masters of the universe were but pebbles in a stream.

Vietnam

America’s defeat at the hands of indigenous troops dressed in black pajamas brought the simplistic military calculus into question. A systems view provided better explanations of how the world worked. Counting things up did not make them real. Whiz kids at the Pentagon were too distant to understand the context. The military machine turned out not to be a machine at all.

Living systems

Organizations are living systems, not machines. The people within them are sentient, emotional, and often irrational human organisms. How they learn is anything but concrete and lockstep. Dipping into the rapid flow of knowledge streaming by, workers pull up a ladle of knowledge never seen before, but knowledge of a world now downstream. The ADDIE model breaks down in times of change or when we no longer buy the concept that an expert needs analyst can somehow suck the important knowledge out of a subject matter expect and encapsulate it into a training intervention. Furthermore, it is folly to imagine that anyone can “control” other human beings. We can give them a little shove here and there but that’s about it.

Landscape design

Put on your sun hat and boots, for we’re going to look at the site for our garden. Permit me the liberty of comparing our landscape project with nature at large and with a corporate organization since both are living systems:

The Designer's Role

As a landscape designer, my goal is to conceptualize a harmonious, unified, pleasing garden that makes the most of the site at hand. As an enlightened instructional designer, my goal is to create a learning environment that advances the organization’s mission by nurturing the growth of its people.

Unity

Great gardens express a unity of design. Gardens are whole, not a series of independent pieces. Unity “is a quality found in all great landscapes, based on the rhythm of natural land-form, the domination of one type of vegetation and the fact that human use and buildings have kept in sympathy with their surroundings. All the great gardens of the world have a unity both of execution and conception which shows that they were created in singleness of thought.” (Crowe, 1994)

Learnscapes

Learning environments, which I’ll dub learnscapes, are like landscapes. They make sense as a whole, not simply a bunch of independent courses and workshops. As in nature, you don’t get very far if you think only of people, ignoring the community in which they are interconnected. We can establish the starting conditions, but then we have to let the plants (or the people) grow as they will. Each organism contains it own feedback loops; adaptation is their destiny. Shouting at them won’t turn roses into rhubarb or artists into engineers, for a rose is a rose is a rose, and a person comes with hard-wired aspects as well as flexibility.

Out of control

Shouting at it does not shorten an organism’s route to maturity. Things grow by the pace of their own internal clock. Gardeners don’t control plants, and managers don’t control people. The most that either can do is nurture growth by supplying nutrients and pulling weeds. Gardeners and managers have influence but not absolute authority. They can’t make a plant fit into the landscape or a person fit into a team.

Fuzzy picture of outcomes

Because landscapes and learningscapes are co-created with nature, the designer never knows precisely what to expect. Photorealistic predictions of the future appearance of gardens and organizations are folly. The designer must work to satisfy aspirations and values, not precise outcomes. Man plans; God laughs. No learnscape will survive when the levee breaks or the ground quakes.

Processes, not events

The late Peter Henschel, former head of the Institute for Research on Learning, said that “The manager’s core work in this new economy is to create and support a work environment that nurtures continuous learning. Doing this well moves us closer to having an advantage in the never-ending search for talent.” How else could it be? Neither nature nor the workplace will cooperate by going into suspended animation so we can tweak the details without things changing all the time. Everything flows. You go with the flow or you are out of it. Every learnscape has a history and a future, but the present is a moving target. (Peter Henschel, in LiNEzine).

Learning = work, work = learning

In a knowledge economy, learning and work are one and the same. Here’s Peter Henschel again, saying “By sheer force of habit, we often substitute training for real learning. Managers often think training leads to learning or, worse, that training is learning. But people do not really learn with classroom models of training that happen episodically. These models are only part of the picture. Asking for more training is definitely not enough—it isn’t even close.”

Oversimplification

Human minds seek to simplify their surroundings. Otherwise the cacophony of waves bouncing off our heads would drive us mad. Deductive reasoning filters reality by rejecting anything that doesn’t fit an if…then…else formula. This is like the behaviorists denying the impact of mental processes because they could not see them.

No shit, Sherlock

Clay Shirky writes that “The great popularizer of this [over-reliance on deductive reasoning] was Arthur Conan Doyle, whose Sherlock Holmes stories have done more damage to people's understanding of human intelligence than anyone other than Rene Descartes. Doyle has convinced generations of readers that what seriously smart people do when they think is to arrive at inevitable conclusions by linking antecedent facts. As Holmes famously put it ‘when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.’"

How we think

He continues, “In the real world, we are usually operating with partial, inconclusive or context-sensitive information. When we have to make a decision based on this information, we guess, extrapolate, intuit, we do what we did last time, we do what we think our friends would do or what Jesus or Joan Jett would have done, we do all of those things and more, but we almost never use actual deductive logic.”

Over…for now

Courses end; learnscapes persist. One should stretch an analogy as much as appropriate but no further. Organizations and their members are living things, and the landscape/learnscape analogy invites us to consider nature, symbiosis, interconnections, genetic make-up, adaptation, the change of seasons, and life cycles. People are not plants, so the analogy doesn’t stretch into self-expression, thinking, identity, personality, and other solely human traits.

In the mechanical world, I’d wrap this up with a conclusion. In a natural world, I know that this is but one step on a long journey. Nothing ends. So I’ll end here for now and pick up later when the situation is ripe.

10 Comments:

I like what you are saying. The reasons that education seems to be linear and unbending might also be the product of the technology that the education system is based on - ie paper.

I reckon that the rigidity that we see in education stems back much much further than WWII, Skinner and Sherlock Holmes.

Marginalising the paper technologies in favour of electronic technologies permits more individual approaches to learning. That in itself will change education as we know it. The role of schools will be to teach how to access, USE and CREATE knowledge on the one hand AND on the other - SOCIAL intelligence.

while education remains so closely tied to economics we're going to find it hard to remove the concepts of performance indicators, milestones and mearsurable outcomes - which all tend to dictate a linear learning pathway if they're to be achived within a specified time period.

Don't get me wrong, I'm all in favour of a good socratic education, I just don't think it can happen in our short sighted capitalist society.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

Jay, have you ever heard of cognitive learning theory? All the cool training developers are using it now. Skinner's box is so... square.

wara,

IIRC my history lessons, the (very) ancient Greeks were severely mistrustful of writing thoughts down on paper, because that somehow corrupted their evanescent purity. Of course, it also allowed them to be shared beyond speaking range and preserved beyond living memory. Without paper (and presses), the Reformation and the Revolution could not have happened. Besides, paper is a heck of a lot cheaper and accessible than electronics.

shaggy,

What do you say about the hordes of people coming to the capitalist USA to get an education to take back with them to help their nascent capitalist economies compete globally?

In the tweeded and tenured academy, one must have *the* Ph.D. to be taken seriously. One must also publish in the right journals and be cited often. But of course, those aren't "performance indicators, milestones and mearsurable outcomes," are they?

Corrie, yes, I'm quite familiar with advances in learning theory. The point of my post is that few designers of learning experiences take it into account. Behaviorism ranks down there with astrology and "intelligent design" in my book, but I encounter it all the time in the business world.

jay

You're tossing the baby out with the bathwater. For certain well-defined domains - almost anything involving muscle memory, or simple factual recall, for example - behaviorism *works*. While it is important to avoid he "igneous fusion" trap of teaching concepts and principles as mere factoids, there are cases where a behaviorist approach is the most practical.

The dynamic, selectionist approach of Skinner's behaviorism has next to nothing in common with the behaviorism that is referred to here. (Social intelligence, on the other hand - now there'sn astrological concept).

Skinner termed his approach "Radical behaviorism", precisely to admit the study of behavior to comprehend thoughts, words and feelings. Get your facts right.

Getting my facts straight.

"...radical behaviorism stops short of identifying feelings as causes of behavior. Among other points of difference were a rejection of the reflex as a model of all behavior and a defense of a science of behavior complementary to but independent of physiology." (Wikipedia)

"Skinner's view of behavior is most often characterized as a "molecular" view of behavior, that is each behavior can be decomposed in atomistic parts or molecules. This view is inaccurate when one considers his complete description of behavior as delineated in the 1981 article, "Selection by Consequences" and many other works. Skinner claims that a complete account of behavior involves an understanding of selection history at three levels: biology (the natural selection or phylogeny of the animal); behavior (the reinforcement history or ontogeny of the behavioral repertoire of the animal); and for some species, culture (the cultural practices of the social group to which the animal belongs). This whole organism, with all those histories, then interacts with its environment." (Ibid)

I have learned several things from this thread. Thanks, Corrie, for the reminder that behaviorism works for activites like memorizing facts. And thanks, R. Gee, for noting that Skinner was somewhat more open-minded than his behaviorist forebears.

Reminds me of that Far side cartoon where one amoeba says to the other one, "Stimulus, response. Stimulus, response. That's all you ever think about!"

M. David Merrill tells a story from his grad school days of a grinding "Theory of Mathematics" course. The material was utterly incomprehendable. The entire class failed the midterm. Dave kept studying and going to class, trying to wrap his brain around the concepts. The final exam was one question: "Describe in detail a system of mathematics."

Dave took a deep breath and figured that he either understood it or not. He took up his pencil and wrote, "Let there be an oar and a rubber boot...." and proceeded to derive rules for addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, commutative and additive properties, etc.

"Educational theories are just oars and rubber boots," he said. (I'm paraphrasing from my memory of the conversation.) "They're useful only as far as they are useful to help build things that work in the real world. If you can come up with a better oar and rubber boot than what I have, show me."

"Stimulus-response" is an oar and a rubber boot. It's useful to a point, and no further. Same with "socially-constructed knowledge." As an instructional designer, I try to build things that work. Whether or not it fits a pre-determined model or theory is a very distant second.

Identifying feelings as "causes" of behavior is indeed not the radical behaviorist way, as this stops short of trying to answer in any useful way the question of what caused the feeling. Initiating causes of behavior are sought in the environment, and any complete account must describe relations between environmental events and the behavior (including emotion or thought) that is functionally related to it. Radical behaviorism considers molar as well as molecular interpretations of behavior - environment relations.

Post a Comment

<< Home